Creating an Opioid Stewardship Committee is one of the critical first steps for hospitals and health systems seeking to play a more active and formal role in combatting the national opioid epidemic. This multidisciplinary internal committee serves as the underlying foundation to the hospital or health system’s overall opioid stewardship effort, providing important structure, leadership and accountability.

Within individual health systems, many efforts are led by multi-disciplinary safety committees composed of physician leadership, pharmacists, and other health system leaders. These teams identify problematic trends, assess evidence, and craft interventions that can be broadly implemented within different health settings. While there is no single method for designing a comprehensive health system approach to safe prescribing, examples of coordinated approaches often incorporate provider education, prescribing guidelines, risk-assessment tools, monitoring and coordination through electronic medical record (EMR) integration, and interventions to positively change provider or patient behavior.

“Strategies for Promoting the Safe Use and Appropriate Prescribing of Prescription Opioids,” Duke Margolis Center for Health Policy, February 2018

Although there is no shortage of recommendations and guidance about opioid stewardship programs in general – including toolkits from the American Hospital Association and others – far less has been published to date around considerations and strategies when establishing the internal opioid stewardship committee.

Part of the reason for this gap is likely due to the fact the structure of the committee (oversight, participants, responsibilities, subgroups, etc.) depends heavily on several factors that are unique to the hospital or health system:

- The overall goals of the opioid stewardship program

- The scope of the effort (i.e., broad vs. targeted)

- The specific needs of the community

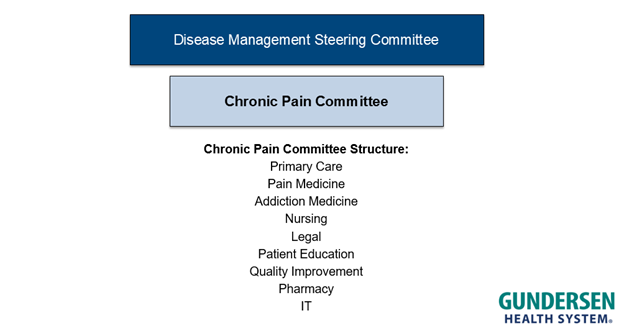

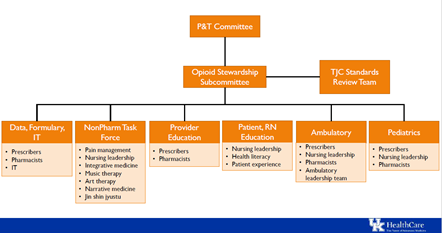

Although published examples of best practices when creating an opioid stewardship are somewhat anecdotal – limited to a slide in a presentation or a few sentences in a report – one commonality is the multidisciplinary nature of the team. In addition to support and engagement from C-level executives, pharmacy leadership is almost always actively involved on the committee, as are representatives from departments that prescribe opioids (primary care, surgery, etc.) or that treat addiction. Participation from nursing leadership and behavioral health stakeholders is also common.

Given that technology and data are foundational to virtually any aspect of an opioid stewardship program – whether it is identifying at-risk patients or building dashboards to monitor opioid prescribing practices – it is critical that IT be engaged from the start. IT leadership should have a formal role on the hospital or health system’s opioid stewardship committee, and there should be active IT participation and representation in any relevant subgroups or “task forces” that report up to the stewardship committee. IT’s involvement on the committee will be essential to succeed with opioid stewardship efforts such as:

- Performing risk modeling to identify vulnerable patients

- Building dashboards and decision support tools to monitor opioid prescribing practices

- Providing standard and/or customized educational content to patients about opioid use

- Developing and implementing order sets and care plans

- Configuring alerts at the point of care to notify clinicians about potential opioid misuse

- Implementing electronic prescribing for controlled substances (EPCS)

- Integrating with the state’s prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) database

| Table 1. Leaders from many different departments or business units serve on opioid stewardship committees. The specific makeup of participants depends on the scope and goals of the opioid stewardship program. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Addiction medicine | Legal/Compliance | Primary care |

| Anesthesiology | Nursing | Process improvement |

| Behavior health | Nutrition | PT/OT |

| Department of Medicine | Pain management | Quality and Safety |

| Emergency department | Patient education/advocacy | Supply chain |

| Hospital administration (CMO/CQO/CIO) | Pediatrics | Surgery |

| IT/IS | Pharmacy | |